FORMATIONS FOR BATTLE....OR NOT......

There is a lot of ink splashed around describing more or less complex formations that could b e adopted by Dark Age armies. After reading all possible ancient texts I find that these accounts are wishful thinking based upon medieval fantasy or are lazy repetition of modern authors doing the same. Two modern sources are most to blame, Paddy Griffith's 'Viking Warfare'(1995) and Osprey's on 'Viking Hersir'(Warrior 3) and 'The Vikings'(Elite 3).

Griffith's book lists Saxo as a source but does not discuss obvious episodes where the behaviour of Viking armies is discussed. He also cites vicariously, meaning he took other authors' excerpts instead of directly citing Saxo himself. I doubt he ever read Saxo at all.

Viking Hersir - by Mark Harrison(1993) , and The Vikings(1985) - by Ian Heath both seem to echo the brief summary given many years before by Foote and Wilson(1970). Neither gives Saxo as a source but Heath does, at least, mention Flateyarbok.

Add to these erroneous accounts the kind of tosh made at great expense for the TV and one can see that the casual reader is easily led into the idea of Viking Armies competing with the Trooping of the Colour to adopt outlandish formations. Authors such as Kim Siddorn and Martina Sprague uncritically perpetuate the myth. Even the latest offerings in this genre, 'Vikinger i Krig' by Hjardar and Vike(2011) and 'Viking Warfare'(2012) by I.P. Stephenson regurgitate this error. Reenactors perpetuate the myth because it looks 'cool'.

But modern authors and reenactors are not alone in their penchant for anachronism. If we look at secondary medieval sources for the Viking Age they positively adopted it as a means of adding credibility and authenticity to their accounts. We must remember that medieval authors were not scholars of history seeking kernels of truth from original sources. They were creators of the truth by virtue of compiling textual corroboration into works of literary art.

Griffith's book lists Saxo as a source but does not discuss obvious episodes where the behaviour of Viking armies is discussed. He also cites vicariously, meaning he took other authors' excerpts instead of directly citing Saxo himself. I doubt he ever read Saxo at all.

Viking Hersir - by Mark Harrison(1993) , and The Vikings(1985) - by Ian Heath both seem to echo the brief summary given many years before by Foote and Wilson(1970). Neither gives Saxo as a source but Heath does, at least, mention Flateyarbok.

Add to these erroneous accounts the kind of tosh made at great expense for the TV and one can see that the casual reader is easily led into the idea of Viking Armies competing with the Trooping of the Colour to adopt outlandish formations. Authors such as Kim Siddorn and Martina Sprague uncritically perpetuate the myth. Even the latest offerings in this genre, 'Vikinger i Krig' by Hjardar and Vike(2011) and 'Viking Warfare'(2012) by I.P. Stephenson regurgitate this error. Reenactors perpetuate the myth because it looks 'cool'.

But modern authors and reenactors are not alone in their penchant for anachronism. If we look at secondary medieval sources for the Viking Age they positively adopted it as a means of adding credibility and authenticity to their accounts. We must remember that medieval authors were not scholars of history seeking kernels of truth from original sources. They were creators of the truth by virtue of compiling textual corroboration into works of literary art.

|

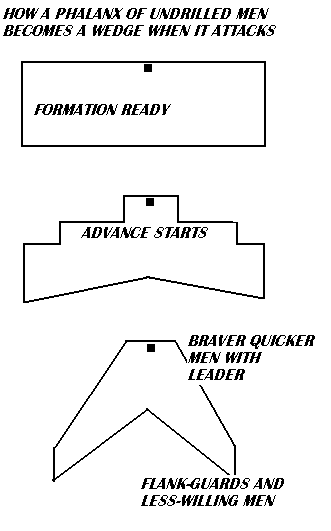

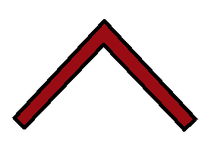

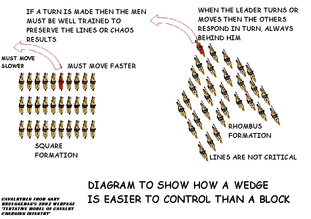

The Boar Snout

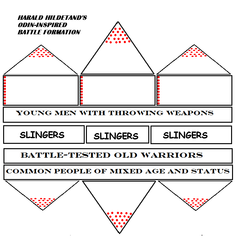

Also known as the 'Boar's Head', 'Svinfylking'(Boar Formation) or simply a 'Wedge'. There is no evidence this formation - whatever it may have been - was used by a Viking Age army. Confusion or conflation may have originally resulted from poor or wilfully creative translation of Asser's account of Alfred the Great at the battle of Ashdown - Chapter 38. Here he states Alfred led his forces forward 'viriliter aprino', 'courageously, like a wild boar'. The 'Natural ' Wedge There may be something in the idea of a wedge forming from a natural tendency for a moving undisciplined phalanx to lose its original line. If this idea holds, the line's wings hang back because the leader is in the centre and the men further away have less incentive to rush on to possible death - being out of the leader's eye - and more incentive to hang back and avoid any danger of being out-flanked. As he leads his originally linear shieldwall on, the war-leader ends-up being at the head of a wedge-shaped column of men who are increasingle less beligerent away from the tip. But this is NOT the wedge given in Norse sources. The Classical cuneus A wedge does exist in the form of the Roman 'caput porcinum' - mentioned by Flavius Vegetius Renatus c.390AD)(19), the 'suos kafale' of Agathias (2.8.8) or the 'caput porci' of Ammianus (17.13.9) - which was an infantry wedge. It is clear from Vegetius that the function is to break a line - and that it emphatically relies upon a deluge of missiles to allow it to penetrate the enemy formation. More attention is given to counter-measures than how to form it. See HERE for texts. The most detailed account of a wedge -shaped formation come from the Strategikon of Maurice where the whole battle-line forms a 'forward-angled half-square, or epikampias emprosthia. Roman super-heavy cavalry made a wedge-shaped formation and other examples exist from cavalry in the era of Alexander the Great. A triangular formation was actually easier to command and manooeuvre for cavalry. The formation can look forward to see what the leader is doing and follow his turns easily. The formation can flex and form as it turns and when set into combat the flanks merely advance until in contact as a line if resistance is met. Cavalrymen can actually fling footmen to the side and horses will not meet breast-to breast but a flinching opposition will turn or split allowing the wedge to proceed. The 'Archaic' Wedge of Medieval Literature The gifted authors of medieval sagas and histories had a job to do. They had to provide a convincing basis for the ancient histories of their nations. At their disposal were many classical texts. Snorri, for example, was like a Shakespeare of his time, absorbing and recycling a mass of literature and history from continental Europe to blend with the rude history of Iceland into masterworks. Saxo'Grammaticus' - with his obscure Latin - also sought to give a foundation in history to the Danes. Their own version of the Greek and Roman histories. At his time, when Valdemar the Great ruled, Danmark was near its height. It had to have a history to match - and a literary foundation. Saxo provided this verification and authentication of a great past which had led to this great present. His account of Odin giving Harald Wartooth tatcical advice for a formation built of lines and wedges before taking on the Swedes- who he defeats, is reminiscent of the description of the Roman army from Livy. Polybius or Vegetius. Three lines plus auxiliaries and some fancy wedge stuff too. With the reinforcing missile troops it even sounds like Arrian's Acies contra Alani in places. Saxo's text HERE. There is an account from Flateyarbok - written shortly after 1200AD, which echoes Saxo's foray into battle tactics. The svinfylking - 'pig/boar formation' is deliberate ly arranged to achieve a breakthrough but here lacks the fine details of Saxo. The text is HERE. Again, one can read the advice is given before a crucial battle - against Vikings - and the day is won. Re-enactment Wedge ? - Pointless, really... An interesting finding from reenactment fighting is that the wedge is rather out of favour these days and is replaced by a dense group of aggressive warriors called a 'cannonball' or a 'punch group'. The arrangement of a wedge-shaped formation is largely redundant because they are easily countered. It should be remembered that the original 'caput porcinum' of Vegetius, who probably can be blamed for starting this whole saga..relied on a massive discharge of missiles to help it penetrate the enemy line. This is impossible in reenactment fighting. This reinforces the idea that an ancient 'wedge' was oft- times a means to split the enemy line rather than a literally wedge-shaped formation. The term 'cuneus' is often used to mean a massive column rather than something which is wedge-shaped. For example, Geoffrey of Tours describes migrating Franks as moving in such 'cuneii'. It is unlikely he means that warriors, women, children, livestock and waggons formed a triangular battle formation to move across the land. |

|

The' Skjaldborg' (O.N.Shield Fort)

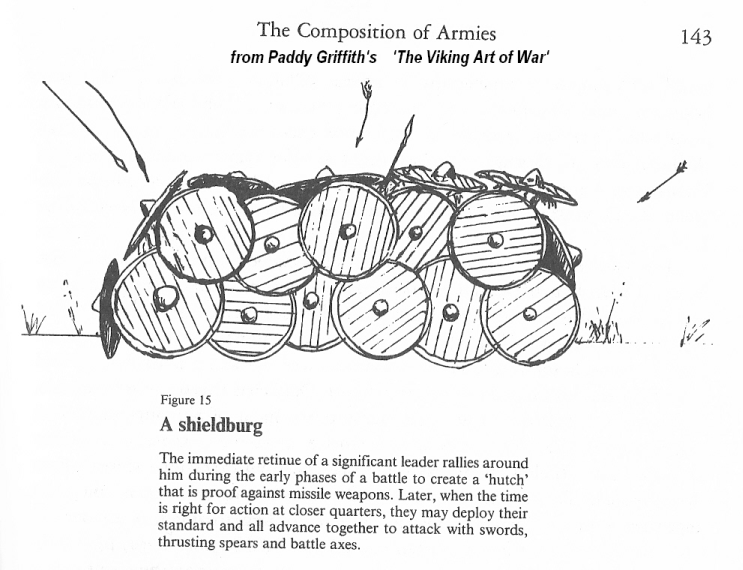

This term is used in medieval sagas as a poetic view of what is probably intneded to be a simple shieldwall. This was reinterpreted by Paddy Griffiths as a kind of 'testudo' used to protect a leader - presumably while he took five and gathered his wits for the next phase of the battle.

It takes maybe five seconds to see the stupidity of such a 'formation'. It is a gift for the enmy to run up and squash all hiding under the shields or to simply surround and massacre them.

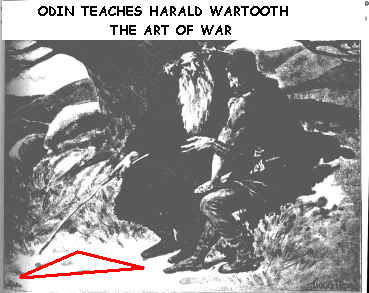

If there is any doubt in your mind as to how much influence the uncritical reliance on secondary source material can have in the general view of a subject take a look at these pictures.

This term is used in medieval sagas as a poetic view of what is probably intneded to be a simple shieldwall. This was reinterpreted by Paddy Griffiths as a kind of 'testudo' used to protect a leader - presumably while he took five and gathered his wits for the next phase of the battle.

It takes maybe five seconds to see the stupidity of such a 'formation'. It is a gift for the enmy to run up and squash all hiding under the shields or to simply surround and massacre them.

If there is any doubt in your mind as to how much influence the uncritical reliance on secondary source material can have in the general view of a subject take a look at these pictures.

|

Another version of a shieldwall from the TV Vikings. Just what this would achieve is open to debate. The shields are horrible, and the leaders waiting to be shot down. |

Richard Fleischer's 1958 film 'The Vikings' was actually more intelligent in its use of the shield fort concept. It was combined with archers to create a spectacular way of providing 'covering fire' for Ragnar's stunt of climbing a castle drawbridge on axes embedded in it. (Watch the film !) |

Gerry Embleton's Wall of Death

The gifted illustrator Gerry Embleton created a powerful image in Plate D of Osprey Warrior 3- Viking Hersir. Reproduced below.

The caption is as follows...

'This reconstruction of a training session at Jomsberg shows the skjaldborg(sic) (shield-wall) arranged in a mutually supporting double line. .......

A senior Jomsviking has chosen this moment to test the strength of the skjaldborg(sic) by attempting to kick on eof the trainees out of position.'

Despite the fact the piece refers to a 'reconstruction' of a scene from a medieval fantasy saga (as was definitvely determined in the 1960s) this image is brought to life today as part of some 'historical' reenactment shows. Without any basis in history. One could just as well ride a motor-cycle over the shields to give a nice display.

There is no Norse source which suggests that a shield wall was ever worked with more than one layer of shields. We have no direct written evidence but several graphic examples such as the 'Warrior Stone' from Gosforth in Cumbria at the top of this page. We do have written evidence from later Roman military manuals for a formation known as the 'phulcum' /fylkon designed to counter missiles (Strategikon XII.B.16.30-38). In such a formation the first rank knelt behind their shields, the second stood close behind and guarded the heads of the first and their own torso and head. The third and subsequent ranks kept their shields high to protect the head and shoulders like a roof. This is actually a close-packed derivation from the usual shield wall. It has nothing to do with 'Viking warfare'.

The caption is as follows...

'This reconstruction of a training session at Jomsberg shows the skjaldborg(sic) (shield-wall) arranged in a mutually supporting double line. .......

A senior Jomsviking has chosen this moment to test the strength of the skjaldborg(sic) by attempting to kick on eof the trainees out of position.'

Despite the fact the piece refers to a 'reconstruction' of a scene from a medieval fantasy saga (as was definitvely determined in the 1960s) this image is brought to life today as part of some 'historical' reenactment shows. Without any basis in history. One could just as well ride a motor-cycle over the shields to give a nice display.

There is no Norse source which suggests that a shield wall was ever worked with more than one layer of shields. We have no direct written evidence but several graphic examples such as the 'Warrior Stone' from Gosforth in Cumbria at the top of this page. We do have written evidence from later Roman military manuals for a formation known as the 'phulcum' /fylkon designed to counter missiles (Strategikon XII.B.16.30-38). In such a formation the first rank knelt behind their shields, the second stood close behind and guarded the heads of the first and their own torso and head. The third and subsequent ranks kept their shields high to protect the head and shoulders like a roof. This is actually a close-packed derivation from the usual shield wall. It has nothing to do with 'Viking warfare'.

Snorri's Ring

In his account of the Battle of Stamford Bridge, 1066, as given in Harald's Saga, Snorri Sturlusson relates that the 'Viking' army of Harald Hardrada took up a special formation. The army stood as a shield wall but with its wings curved back round so that they met at the back - effectively a ring. The king and his retinue stood in the centre with archers and reserves.

The ring so formed is described as of even depth and with 'shields overlapping in front and above'.

In addition, Harald makes special provision that he can send out sorties against the English cavalry that he knows will attack in small detachments. Infantry making sorties against cavalry ?

This is a mostly convincing and detailed account. The only problem is that this is precisely what Snorri is good at. Snorri's account of Stamford Bridge begins to crumble when we read that the English attacked as cavalry. Furthermore it begins to read like a mirror image of his account of Hastings, with the Norwegians playing the role of the English.

We cannot escape the fact that Snorri was a saga writer composing a good story about events more than 200 years earlier. No other texts support his account and noneof those we know he used as his sources.

The ring so formed is described as of even depth and with 'shields overlapping in front and above'.

In addition, Harald makes special provision that he can send out sorties against the English cavalry that he knows will attack in small detachments. Infantry making sorties against cavalry ?

This is a mostly convincing and detailed account. The only problem is that this is precisely what Snorri is good at. Snorri's account of Stamford Bridge begins to crumble when we read that the English attacked as cavalry. Furthermore it begins to read like a mirror image of his account of Hastings, with the Norwegians playing the role of the English.

We cannot escape the fact that Snorri was a saga writer composing a good story about events more than 200 years earlier. No other texts support his account and noneof those we know he used as his sources.