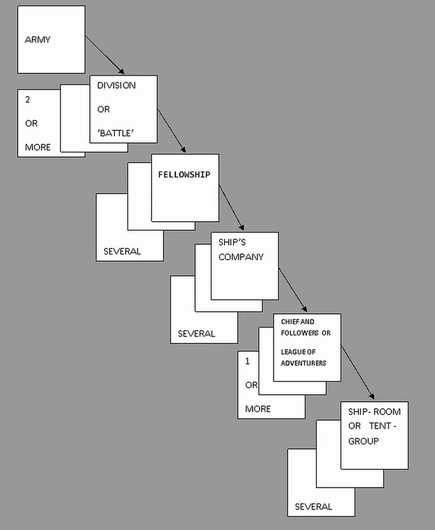

ORGANISATION OF VIKING ARMIES

No military manual survives from a 'viking' source. We must hunt for scraps of information which indicate how armie sof Northmen were organised.

LOWER LEVEL ORGANISATION

Within a large gathering of warriors there must have been some kind of lesser organisation. Otherwise there would have been chaos when arranging movement, food or a battle-line. The simplest explanations have been focused upon kinship groups, the followings of wealthy individuals, bodyguard units and ‘shiploads’. We find no evidence for any of these. No evidence for any small-scale organisation of a ‘Viking’ army. From the later Olaf’s Saga we hear from Snorri that King Olaf preferred that his men stood in ‘flocks’ or ‘parcels’ of folk who knew each other in the battle line at Stiklestad. The poem ‘The Battle of Maldon’ describes the earl’s army as his kinsmen and those from his earldom. when the earl dismounts from his horse to fight he joins the shieldwall amongst his hearth-companions or bodyguard. One earl could not reasonably be expected to have more than 36 men paid from his own pocket - our shipload - as his paid bodyguard. such a number need their own hall to live in, food al year and equipment. The largest bodyguard or private contingents we hear of are up to 300 strong- those of emperors or great generals such as Count Belisarius of Byzantium. Perhaps this 36 could be an indication of how many warriors could be commanded by one unexceptional leader in the battle line. Taking to reenactment evidence for a moment it can be said that to control more than 36 men with one’s voice and presence on a battlefield is an extremely difficult task.

Seeing as how the Viking armies often seem to have moved by ship then perhaps the scale of a ship-s crew is a clue here. A ship requires an owner, a skipper and crew. The smallest ships that could usefully cross the north sea and take something of value home again would approximate to the smaller Skuldelev 5 ship. This has 13 pairs of oars. This also the smallest size of ship from later leidang levy regulations.

In addition, the AS chronicle says that English ships with 60 oars were double the size of most Viking warships in 896. If a few non-rowing nobles or leaders are included then the ship’s contingent might be 30 to 40 men. This gives us a lower limit for a Viking raiding party and accords with the earlier law of Ine of Wessex which recognised the havoc 36 men could cause when he declared this number of armed men to be an army and subject to royal opposition. Any re-enactment society which can field a contingent of 36 should congratulate itself at being able to field a force recognised as useful and dangerous in the dark ages and thus an authentically sized warband.

Later textual evidence identifies 'guilds' or leagues of merchant venturers who shared the risk and profit of foreign expeditions. They were termed felagi and væringi - giving rise to the later term 'Varangian'. Such guilds could have shares in one or more ships.

In Ottonian Saxony of the tenth century the military class seem to have operated in 'banda' or bands of circa 50 men.

Within a large gathering of warriors there must have been some kind of lesser organisation. Otherwise there would have been chaos when arranging movement, food or a battle-line. The simplest explanations have been focused upon kinship groups, the followings of wealthy individuals, bodyguard units and ‘shiploads’. We find no evidence for any of these. No evidence for any small-scale organisation of a ‘Viking’ army. From the later Olaf’s Saga we hear from Snorri that King Olaf preferred that his men stood in ‘flocks’ or ‘parcels’ of folk who knew each other in the battle line at Stiklestad. The poem ‘The Battle of Maldon’ describes the earl’s army as his kinsmen and those from his earldom. when the earl dismounts from his horse to fight he joins the shieldwall amongst his hearth-companions or bodyguard. One earl could not reasonably be expected to have more than 36 men paid from his own pocket - our shipload - as his paid bodyguard. such a number need their own hall to live in, food al year and equipment. The largest bodyguard or private contingents we hear of are up to 300 strong- those of emperors or great generals such as Count Belisarius of Byzantium. Perhaps this 36 could be an indication of how many warriors could be commanded by one unexceptional leader in the battle line. Taking to reenactment evidence for a moment it can be said that to control more than 36 men with one’s voice and presence on a battlefield is an extremely difficult task.

Seeing as how the Viking armies often seem to have moved by ship then perhaps the scale of a ship-s crew is a clue here. A ship requires an owner, a skipper and crew. The smallest ships that could usefully cross the north sea and take something of value home again would approximate to the smaller Skuldelev 5 ship. This has 13 pairs of oars. This also the smallest size of ship from later leidang levy regulations.

In addition, the AS chronicle says that English ships with 60 oars were double the size of most Viking warships in 896. If a few non-rowing nobles or leaders are included then the ship’s contingent might be 30 to 40 men. This gives us a lower limit for a Viking raiding party and accords with the earlier law of Ine of Wessex which recognised the havoc 36 men could cause when he declared this number of armed men to be an army and subject to royal opposition. Any re-enactment society which can field a contingent of 36 should congratulate itself at being able to field a force recognised as useful and dangerous in the dark ages and thus an authentically sized warband.

Later textual evidence identifies 'guilds' or leagues of merchant venturers who shared the risk and profit of foreign expeditions. They were termed felagi and væringi - giving rise to the later term 'Varangian'. Such guilds could have shares in one or more ships.

In Ottonian Saxony of the tenth century the military class seem to have operated in 'banda' or bands of circa 50 men.

HIGH LEVEL ORGANISATION

At higher levels the only evidence we have for army organisations are from a few comments about how the Viking armies are led.

Viking forces whether they are designated armies or not, are said to be led by kings. These kings cannot have been the king of Norway, Denmark or small portions of it. Even in Snorri there are not so many kings around and if kings are spending years away in France and England what is happening to their kingdoms at home ? These men are not kings at home but the magnates or warlords who have come to lead the aggregates of treasure and land-seekers that form the Viking armies. Men leading such large forces are naturally referred to as kings by the chroniclers. The presence of more than one king indicates we have a composite force. Thus the ‘Great Army’ of the late 860’s which was led by 3 kings and also included a number of lesser earls can be seen to have been an unusually large force because it was a confederation of different groups. The great army later splits up. The large army which wintered at Repton in 873-4 comprised a -summer army- and the core of the earlier great army which had settled in East Anglia. It later divided again in 874-5. From Frankish chronicles we hear of a Viking force led by one Weland who assembles a great fleet by gaining the cooperation of another Viking force and then divides this great force into ’sodalites’ or ‘groups of companions’ in order to overwinter without taxing any one location too much.

The armies that raided Francia and met the English at Brunanburgh and the Great Army itself probably came from different areas - not just Scandinavia and certainly not just Denmark. They came from Irish colonies, Scotland, and could include other nationalities. Some were -new arrivals- and some veterans of several years campaigning with the army.

We can probably say that the -armies- of Vikings before the age of kings were, in reality, confederations of different groups with common interests. Their origin, nature and ultimate aims were different but they were willing to coalesce in order to allow the possibility of great gains in competition with the English kingdoms and the Frankish Empire. Raiding may pay in the short term but was too risky once the English and the Franks became aware of the problem. The largest armies probably numbered less than 10,000 men, maybe many less than this. The more common -raiding force- that formed the building blocks of such armies was the crew and passengers of a small number of ships - maybe 300 men at most and often less. Alfred-s navy dealt with a raiding force in 896 that comprised 6 ships and about 240 men.

According to Alfred’s biographer, Asser, the Vikings at Ashdown , were divided into two shield walls, having two kings with them and several earls. The core of their army was assigned to the two kings, the rest to the earls - we cannot even say if this divison corresponds to that first mentioned. The English copied this deployment, with Alfred taking one division and his brother Aethelred the other. We cannot say if the two divisions stood side by side or one behind the other. Later that year 871 at Marden were the Viking army army again in two divisions.

An interesting account in Geoffrey of Tours’ History of the Franks describes how the Saxon army crossing Frankish territory in divided into two -wedges- which may just indicate great columns. Perhaps there was a basic principle here that an army should form more than one body in order to avoid defeat en-block, or to allow some minimal tactical responsiveness - one division could manoeuvre while the other fought or advanced.

At higher levels the only evidence we have for army organisations are from a few comments about how the Viking armies are led.

Viking forces whether they are designated armies or not, are said to be led by kings. These kings cannot have been the king of Norway, Denmark or small portions of it. Even in Snorri there are not so many kings around and if kings are spending years away in France and England what is happening to their kingdoms at home ? These men are not kings at home but the magnates or warlords who have come to lead the aggregates of treasure and land-seekers that form the Viking armies. Men leading such large forces are naturally referred to as kings by the chroniclers. The presence of more than one king indicates we have a composite force. Thus the ‘Great Army’ of the late 860’s which was led by 3 kings and also included a number of lesser earls can be seen to have been an unusually large force because it was a confederation of different groups. The great army later splits up. The large army which wintered at Repton in 873-4 comprised a -summer army- and the core of the earlier great army which had settled in East Anglia. It later divided again in 874-5. From Frankish chronicles we hear of a Viking force led by one Weland who assembles a great fleet by gaining the cooperation of another Viking force and then divides this great force into ’sodalites’ or ‘groups of companions’ in order to overwinter without taxing any one location too much.

The armies that raided Francia and met the English at Brunanburgh and the Great Army itself probably came from different areas - not just Scandinavia and certainly not just Denmark. They came from Irish colonies, Scotland, and could include other nationalities. Some were -new arrivals- and some veterans of several years campaigning with the army.

We can probably say that the -armies- of Vikings before the age of kings were, in reality, confederations of different groups with common interests. Their origin, nature and ultimate aims were different but they were willing to coalesce in order to allow the possibility of great gains in competition with the English kingdoms and the Frankish Empire. Raiding may pay in the short term but was too risky once the English and the Franks became aware of the problem. The largest armies probably numbered less than 10,000 men, maybe many less than this. The more common -raiding force- that formed the building blocks of such armies was the crew and passengers of a small number of ships - maybe 300 men at most and often less. Alfred-s navy dealt with a raiding force in 896 that comprised 6 ships and about 240 men.

According to Alfred’s biographer, Asser, the Vikings at Ashdown , were divided into two shield walls, having two kings with them and several earls. The core of their army was assigned to the two kings, the rest to the earls - we cannot even say if this divison corresponds to that first mentioned. The English copied this deployment, with Alfred taking one division and his brother Aethelred the other. We cannot say if the two divisions stood side by side or one behind the other. Later that year 871 at Marden were the Viking army army again in two divisions.

An interesting account in Geoffrey of Tours’ History of the Franks describes how the Saxon army crossing Frankish territory in divided into two -wedges- which may just indicate great columns. Perhaps there was a basic principle here that an army should form more than one body in order to avoid defeat en-block, or to allow some minimal tactical responsiveness - one division could manoeuvre while the other fought or advanced.

ORGANISATION OF A 'VIKING' ARMY

The ship-room was the space between the ribs of the ship where each oar place was situated. It was thus occupied by 2 oarsmen plus a share of extra men allotted to the ship.

A tent-group is a hypothetical ‘building brick’ of a few men who know each other, who mess and fight together and are comrades-in arms.