ARMIES IN BATTLE

An army could be 36 men according to early English Law. This shows how vulnerable early nations were to an organised armed band. We must take a more sophisticated definition, however, and something like ' a cooperating force of several organised groups of fighting men' is more useful. Such a force could range in size from a few hundreds to several thousands. Armies in the order of tens of thousands were not available even to the largest states of the time.

|

An ordered arrangement of isolated units waiting to coordinate their manoeuvres on the field of battle are, for the Viking Age no less than 'science fiktion', as the Scandinavian phrase has it.. |

A shieldwall implies one continuous line presented to the enemy. Indeed, any break in a shieldwall is a vulnerability which could let the enemy in, so we should not imagine a Napoleonic type line-up for a Viking Age army. |

At Ashdown in 871AD the English saw the Danes had made two equal divisions - each a shieldwall. One was led by 'kings' the other by 'earls'. The English did the same - made two shieldwalls to take on each enemy division. This seems to indicate two divisions on a common front rather than one division held in reserve.

The same two-division battle-line was presented at Marden later in the same year. Maybe this indicates a Danish army split with irreconcilable differences.

The Roman military manuals never recommend splitting a battle line. What we see here is an essentially tribal army with higher concerns than military efficiency dictating their tactics.

It was more important that the relevant leaders led their men on the battlefield than to submit their forces to control of another.

The same two-division battle-line was presented at Marden later in the same year. Maybe this indicates a Danish army split with irreconcilable differences.

The Roman military manuals never recommend splitting a battle line. What we see here is an essentially tribal army with higher concerns than military efficiency dictating their tactics.

It was more important that the relevant leaders led their men on the battlefield than to submit their forces to control of another.

GETTING TO GRIPS

The 'army' needed to first locate the enemy and gain intelligence in order to fight with them. Viking armies used scouts, mounted where possible. These would report back to the commanders. In addition we could imagine that information would be gained 'informally' by foragers returning to camp each day and by the interrogation of locals.

Intelligence would be used first and foremost to avoid a pitched battle. An army on hostile territory which is defeated risks annihiliation. The number one tactic of viking armies was simply not to fight. A raid, a night attack or rapid relocation were preferable to meeting the enemy in open battle. Only if flight was unavoidable or if the odds were in their favour would a battle occur. It must be remembered that they were usually in a foreign land and always tried to create some insurance for their safe escape from defeat. Fugitives in a foreign land usually get short shrift from the natives.

The 'army' needed to first locate the enemy and gain intelligence in order to fight with them. Viking armies used scouts, mounted where possible. These would report back to the commanders. In addition we could imagine that information would be gained 'informally' by foragers returning to camp each day and by the interrogation of locals.

Intelligence would be used first and foremost to avoid a pitched battle. An army on hostile territory which is defeated risks annihiliation. The number one tactic of viking armies was simply not to fight. A raid, a night attack or rapid relocation were preferable to meeting the enemy in open battle. Only if flight was unavoidable or if the odds were in their favour would a battle occur. It must be remembered that they were usually in a foreign land and always tried to create some insurance for their safe escape from defeat. Fugitives in a foreign land usually get short shrift from the natives.

An army would then form-up for a fight in a suitable place. Ideally there would be some covering terrain to the rear which would make running away easier if it was necessary. Even better, one or more of the flanks would also be protected. If the whole army could be situated on high ground, so much the better.

At Ashdown in 871AD the Danes facing King Æthelred took the chance to deploy their army first, on higher ground.

At Ashdown in 871AD the Danes facing King Æthelred took the chance to deploy their army first, on higher ground.

SIEGE AND SALLY

There are not many true sieges in the Viking Age. The failed attempt on Paris indicates the problems faced by an ad hoc force with divided command in a foreign land.

In the Viking Age a force would trap another in a fortified place but it was rare that a true siege was mounted over any length of time. The forces of the day were not numerous enough nor had sufficient engineering skills to isolate and enter a defended fort.

In 867AD the Northumbrian army attacked the Danes in York. The English managed to break down the wall and pursue the Danes inside but only because at that time there wer eno firm and secure walls - as Asser says.

In 877AD Alfred's mounted forces pursued the Danes - also mounted - to Exeter but found themselves unable to get in. The Danes, however, came to terms as they were blockaded.(ASC)

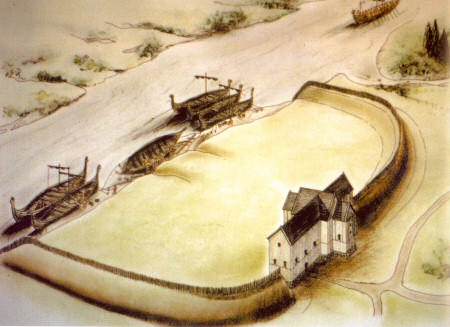

Viking armies would use a town, monastery or fort or fortify a suitable - maybe ancient - defensible site.

Of course, sitting in an impregnable position is not conducive to offensive tactics and Scandinavian forces could attack when necessary.

When confronting a force in a defended place the besieger is always vulnerable to being attacked when dispersed.

When faced with a besieging force, an army in even an ideal fortress can be subdued merely because they do not have sufficient supplies or are forced to negotiate rather than fight.

At Reading in 871AD the Danes occupying the burg - a fortress town - sallied out to take on their would-be besiegers and won a victory.

In 873AD the English did the same to the Dane at Cynuit in Devon. A sloppy siege was routed.

There are not many true sieges in the Viking Age. The failed attempt on Paris indicates the problems faced by an ad hoc force with divided command in a foreign land.

In the Viking Age a force would trap another in a fortified place but it was rare that a true siege was mounted over any length of time. The forces of the day were not numerous enough nor had sufficient engineering skills to isolate and enter a defended fort.

In 867AD the Northumbrian army attacked the Danes in York. The English managed to break down the wall and pursue the Danes inside but only because at that time there wer eno firm and secure walls - as Asser says.

In 877AD Alfred's mounted forces pursued the Danes - also mounted - to Exeter but found themselves unable to get in. The Danes, however, came to terms as they were blockaded.(ASC)

Viking armies would use a town, monastery or fort or fortify a suitable - maybe ancient - defensible site.

Of course, sitting in an impregnable position is not conducive to offensive tactics and Scandinavian forces could attack when necessary.

When confronting a force in a defended place the besieger is always vulnerable to being attacked when dispersed.

When faced with a besieging force, an army in even an ideal fortress can be subdued merely because they do not have sufficient supplies or are forced to negotiate rather than fight.

At Reading in 871AD the Danes occupying the burg - a fortress town - sallied out to take on their would-be besiegers and won a victory.

In 873AD the English did the same to the Dane at Cynuit in Devon. A sloppy siege was routed.

A LITTLE SOMETHING EXTRA

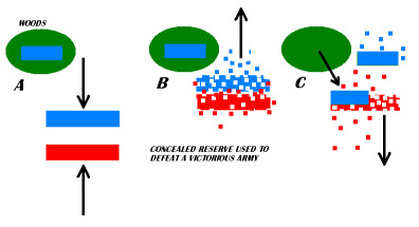

Viking armies appear to have had a card up their soiled sleeves. A card which seems maybe basic and obvious but a cards their enemies rarely managed to play or counter which again serves to show how difficult it was for armies following 'traditional' methods and under heirarchical rather than meritocratic command to buck their prevailing contemporary behaviours. This card was ' reserves'.

A reserve line means simply making two shield walls, one behind the other. Possibly one alongside the other. This tactic seems no tto have been used. Reserves in the Viking context meant a hidden reserve.

A reserve line means simply making two shield walls, one behind the other. Possibly one alongside the other. This tactic seems no tto have been used. Reserves in the Viking context meant a hidden reserve.

|

The hidden reserve is a simple insurance against catastrophic defeat. A force is kept out of sight to intercept enemy pursuing one's own fleeing men. Even a few men who are organised, fresh for battle and who appear at a critical moment can turn the tide of battle decisively or at least give fugitives a chance to get away.

|

At York in 867AD the Northumbrians entering York were overwhelmed by an unexpected Danish counterattack.

STRANGERS IN A STRANGE LAND

On the open battlefield we have no evidence that 'viking' armies behaved any differently from their opponents. Their main additional proccupation was to limit the chances of, and results of defeat. There was no local prestige to be lost by avoiding battle, their forces were loyal and could not return home to work on the farm or need defend their homes against marauders and the day would eventually arise when fortune favoured them so long as they avoided trouble. Perhaps surprisingly, the defending army, on its own soil, of an agricultural society was at a disadvantage because it might suffer from divided loyalties, was pressed for time to limit damage to its own infrastructure and had to defend a wide area with limited resources on limited intelligence about a mobile enemy. In addition, the attacker had the initiative in the days before telecommunications.

ATTACKER'S ADVANTAGES

Leader has already surmounted problems of gathering and organising his army.

Assembled manpower

Focussed loyalties of men and leaders

If mobile can choose place and time for confrontation

Defeat means flight in a hostile land

DEFENDER'S ADVANTAGES

Leader must gather and organise an army in the face of a threat

Reserves of manpower

Differential loyalties of those from nearby and those from far away

Local political intrigues can split command

Ability to fortify from knowledge of places and manpower

Defeated armies gain succour from friendly land

AFTER THE BATTLE

A lost battle could mean total annihilation with the forces and cause of the losers committed to history. Or not.

A win could be claimed by the side which remained in possession of the field of battle or a side which killed the opposing leader.

This is different from a modern Clausewitzian idea that the enemy force should be destroyed and his capital city occupied.

Warfare in the viking age was concerned with the making and pressing of an argument by leaders, not the destruction of the social status quo. An attempt by Frankish commoners to take their defence into their own hands led to them being slaughtered by their own nobility : the social order did not allow the power of the military class to be usurped.

It was difficult to eliminate an enemy because organised pursuit was difficult to achieve after a battle. A defeated army whose leaders remained alive could rally at some safe place a day or so later and continue to pose a threat.

This is why we so often read of seemingly moderate terms agreed by the winners after a large scale battle. It was better for the winners to make a treaty with the losers while they could be forced to negotiate than to have them disappear only to remain a nuisance.

STRANGERS IN A STRANGE LAND

On the open battlefield we have no evidence that 'viking' armies behaved any differently from their opponents. Their main additional proccupation was to limit the chances of, and results of defeat. There was no local prestige to be lost by avoiding battle, their forces were loyal and could not return home to work on the farm or need defend their homes against marauders and the day would eventually arise when fortune favoured them so long as they avoided trouble. Perhaps surprisingly, the defending army, on its own soil, of an agricultural society was at a disadvantage because it might suffer from divided loyalties, was pressed for time to limit damage to its own infrastructure and had to defend a wide area with limited resources on limited intelligence about a mobile enemy. In addition, the attacker had the initiative in the days before telecommunications.

ATTACKER'S ADVANTAGES

Leader has already surmounted problems of gathering and organising his army.

Assembled manpower

Focussed loyalties of men and leaders

If mobile can choose place and time for confrontation

Defeat means flight in a hostile land

DEFENDER'S ADVANTAGES

Leader must gather and organise an army in the face of a threat

Reserves of manpower

Differential loyalties of those from nearby and those from far away

Local political intrigues can split command

Ability to fortify from knowledge of places and manpower

Defeated armies gain succour from friendly land

AFTER THE BATTLE

A lost battle could mean total annihilation with the forces and cause of the losers committed to history. Or not.

A win could be claimed by the side which remained in possession of the field of battle or a side which killed the opposing leader.

This is different from a modern Clausewitzian idea that the enemy force should be destroyed and his capital city occupied.

Warfare in the viking age was concerned with the making and pressing of an argument by leaders, not the destruction of the social status quo. An attempt by Frankish commoners to take their defence into their own hands led to them being slaughtered by their own nobility : the social order did not allow the power of the military class to be usurped.

It was difficult to eliminate an enemy because organised pursuit was difficult to achieve after a battle. A defeated army whose leaders remained alive could rally at some safe place a day or so later and continue to pose a threat.

This is why we so often read of seemingly moderate terms agreed by the winners after a large scale battle. It was better for the winners to make a treaty with the losers while they could be forced to negotiate than to have them disappear only to remain a nuisance.